Semiose

Pieter Jennes , Belgium

"Le Bouquet manquant"

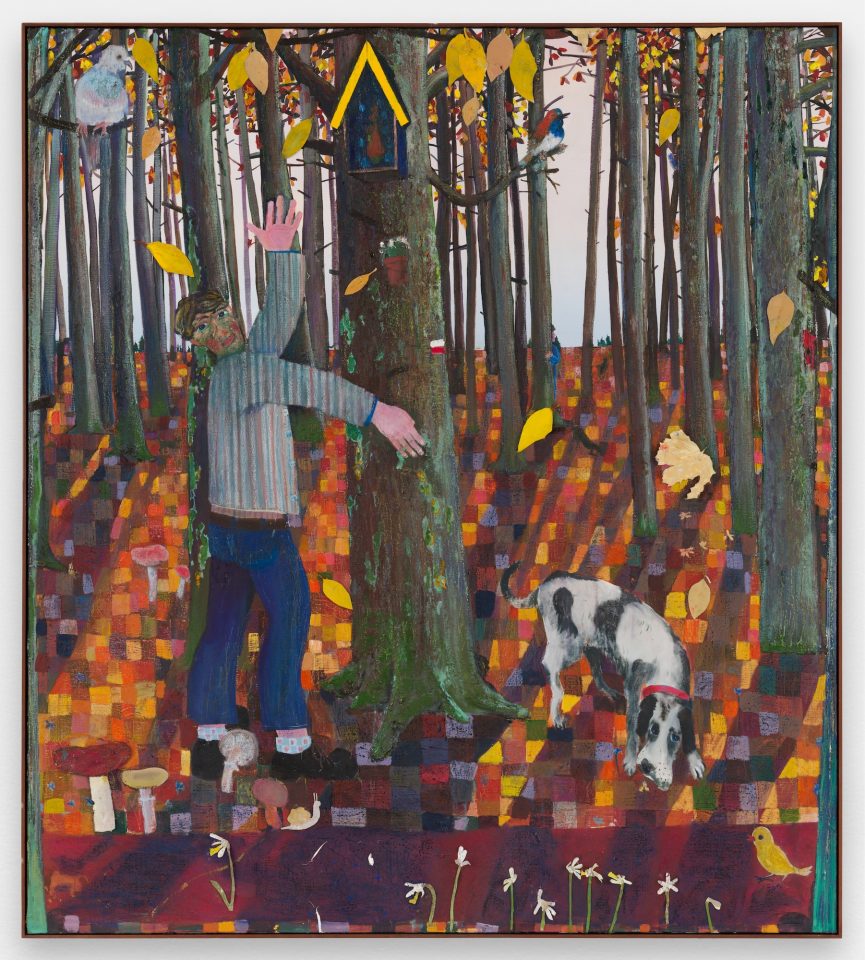

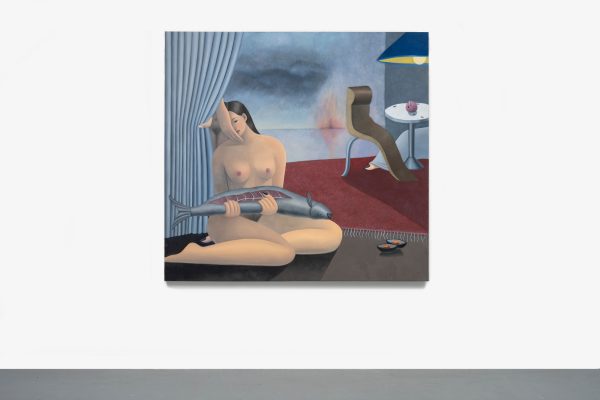

Pieter Jennes, Il me tarde, 2025, Huile et collage sur toile / Oil and collage on canvas 190 × 170 cm / 74 13/16 × 66 15/16 inches 192 × 172 × 4 cm / 75 9/16 × 67 11/16 × 1 9/16 inches (encadré / framed)

Semiose is delighted to present the first exhibition in France of Flemish artist Pieter Jennes. His composite oil paintings and collages are distinguished by their vivid palettes, intricate detail and singular narrative quality. Classic themes – people, animals, nature – are treated in a way that is as touching as it is expressive, probing the full range of human emotions.

Laetitia Chauvin: Where does the title of the exhibition come from?

Pieter Jennes: I chose “Le Bouquet Manquant” because it’s the title of the main work in the exhibition. The painting “Le Bouquet Manquant” shows a boy, surrounded by dogs, picking flowers and distracted by the sight of a butterfly. The title evokes those moments in a relationship when there are unspoken expectations, which may or may not be met. The works in the exhibition deal with love in the broadest sense, but above all with the different stages of a loving relationship.

LC: Even in the painting “Il Me Tarde”?

PJ: This painting shows a boy walking his dog in the forest. In the background, as in the collage of the pregnant girl (Le Bouquet Manquant A), several characters are hiding behind trees, and many of the trees have romantic messages engraved on their trunks. The little blue house is not a nesting box, but rather a little chapel in a tree. In the past, a tree was often planted at a crossroads and given a special meaning by hanging a model chapel on it. Trees have been objects of worship for millennia and, in the eyes of prehistoric man, there was no better symbol of divine life force than the mighty tree. Many cultures tell the story of the tree of life, or the world tree that links heaven, earth and the underworld. It’s often the oak or lime tree that carries this particular meaning.

LC: In “Untitled”, it’s more a question of physical love…

PJ: Indeed, the little rooster does his utmost to give pleasure to the hen. Expressions of physical love like hugs, kisses and caresses are important.

LC: In “Each Person”, on the other hand, there’s a more melancholy side.

PJ: Of course, there’s a sense of nostalgia, of missing or remembering someone… In this painting, the boy is looking out of the window, lost in thought. He’s clearly somewhere else in his mind, but in my opinion, he’s not sad, he can even smile a little. On the wall in the background, there are several colorful drawings of romantic scenes. If someone can occupy our thoughts to that extent, our love must be real.

LC: And what about “The Bird”?

PJ: I used to paint a lot of birds. I grew up near a forest and my father is a birdwatcher. Like the painter’s collage, the bird is a silent witness. Although the expression is no longer commonly used, “a bird” also refers to an attractive woman.

LC: In fact, there are birds in almost all your works !

PJ: That’s not deliberate at all. I’ve also often used the fall of people or animals as subjects for my drawings and paintings. This stems from my fascination with the Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader (1942-1975), who frequently explored the effects of gravity or falling in his small but powerful work. Birds perhaps symbolize the opposite of this phenomenon, in their ability to defy gravity.

LC: Your work is full of tiny details, such as flowers, apple cores, leaves, butterflies, dragonflies, etc., and even tiny trees in the landscape. You play with different scales to build a composition where natural elements have a predominant place.

PJ: I grew up in the countryside, then lived in the city for a while. I’ve now moved back to the country. The works I’m doing now represent late summer or early autumn, a time when nature is very active. Insects know they’re living their last moments and try to make the most of their remaining life. Animals build up reserves or fatten up for winter. Birds begin to migrate. Due to the fermentation of decaying fruit, it’s not uncommon to find inebriated animals in the forest… In short, life is in full swing!

LC: The exhibition also includes two collages that seem to function as a diptych. One shows a painter at his easel, in front of a blank canvas, the other a woman in the woods. Is the painter a self-portrait?

PJ: It’s more of an archetypal image, but one that expresses everything I am. The second collage shows a pregnant woman walking through the forest with several men hiding behind the trees. When my girlfriend was pregnant, I was fascinated by the changes taking place in her, her body taking on the shape of a balloon. It was great fun to draw and paint, using large circular objects as models.

LC: Your characters are integrated in a curious way into your landscapes, which resemble sets, almost like in theater.

PJ: I have a great affection for illuminated medieval miniatures, which, despite their realism, often seem orchestrated like stage sets. Perspective, while present, is a minor aspect of the image as a whole. When I was an art student, I had access to various heritage libraries where I could browse medieval books and examine miniatures up close, without protective glass. In my particular case, I need reality to be able to create a painting, but the painting doesn’t need to reflect that reality.

LC: You sometimes staple the pieces together in your collages, a rather unusual technique…

PJ: When I first started making collages, I simply used glue, but I was afraid that some pieces would come loose after a while, so I decided to staple them very firmly. Over time, I began to adopt staples because they gave the collages more punch and I liked their aggressiveness, which formed a nice contrast with the often gentle subjects.

LC: One of the characteristics of your work is its particularly matte finish.

PJ: The matte effect of my paintings is achieved by shading with lightfast felt-tip pens and colored pencils. I like the fact that my works absorb light, which is a completely different experience from our everyday interaction with backlit screens.

Solo show of Pieter Jennes

From May 17th to June 21st, 2025

The gallery

Founded in 2007 in the 20th district of Paris before migrating to the Marais area in 2011, from the outset, Semiose established itself in the artistic landscape as a gallery, whose aesthetic values are rooted on the margins of art. Nourished by underground culture, the gallery is committed to forms and ideas born in the political, social and geographical fringes.

The practice of citation is a common reference point for the roster of artists represented by the gallery and raises complex issues related to the production and dissemination of images, the role and purpose of archives and visual culture in the broadest sense. Semiose champions an aesthetic based on questions of taste and consequently of cultural hierarchies. Techniques such as collage, appropriation and cultural subversion are shared by many of the artists, leading to a converging interest in referencing reality and the everyday world.

Younger artists are exhibited side by side with established names and figures of international renown. Over the years and through a patiently developed professional network, various institutions and public collections have forged strong links with artists promoted by the gallery. Semiose however, is committed to much more than simply representing artists: the gallery rigorously fulfills its role in the eco-system of art through its scientific and curatorial approach. It oversees the production of oeuvres and undertakes meticulous documentary and archival work around the artists it represents.

Semiose has also expanded its activities through a publishing house, Semiose éditions. Internationally available, more than a hundred titles have been published to date, including monographs, books by artists, written works and essays, an on-going magazine and a collection of coloring books.

Gallery artists

Salvatore Arancio, Amélie Bertrand, Olaf Breuning, William S. Burroughs, Hugo Capron, Anthony Cudahy, Oli Epp, Steve Gianakos, Sébastien Gouju, Otis Jones, Aneta Kajzer, Laurent Le Deunff, Anne Neukamp, Justin Liam O’Brien, Françoise Pétrovitch, Abraham Poincheval, Présence Panchounette, Laurent Proux, Stefan Rinck, Ernest T., Moffat Takadiwa, Julien Tiberi, Gert & Uwe Tobias, Philemona Williamson, Xie Lei